"NOTHING JUST HAPPENS" - <p>SLOVENIAN LITERATURE ON THE WORLD MAP (part II)

Slovene Writers' Association has 308 members. Very few writers (not all of them are members of the Slovene Writers' Association) can live merely off what they create. They are supported by certain social mechanisms, from giving public lending rights payments whenever their books are borrowed from a library, to work and creative bursaries, all of which relieve their economic situation, but the majority of authors are freelancers or work in other jobs, often making literary creativity their parallel activity.

Translators from Slovene provide quality translations into all major world languages, however there is a certain lack of direct translators into some languages with relatively large and translation-interested book markets such as, for example, Turkish or some Scandinavian languages. The Slovenian Book Agency organizes yearly translation seminars for translators from Slovene into foreign languages to overcome some gaps and to promote Slovene authors to translators as well.

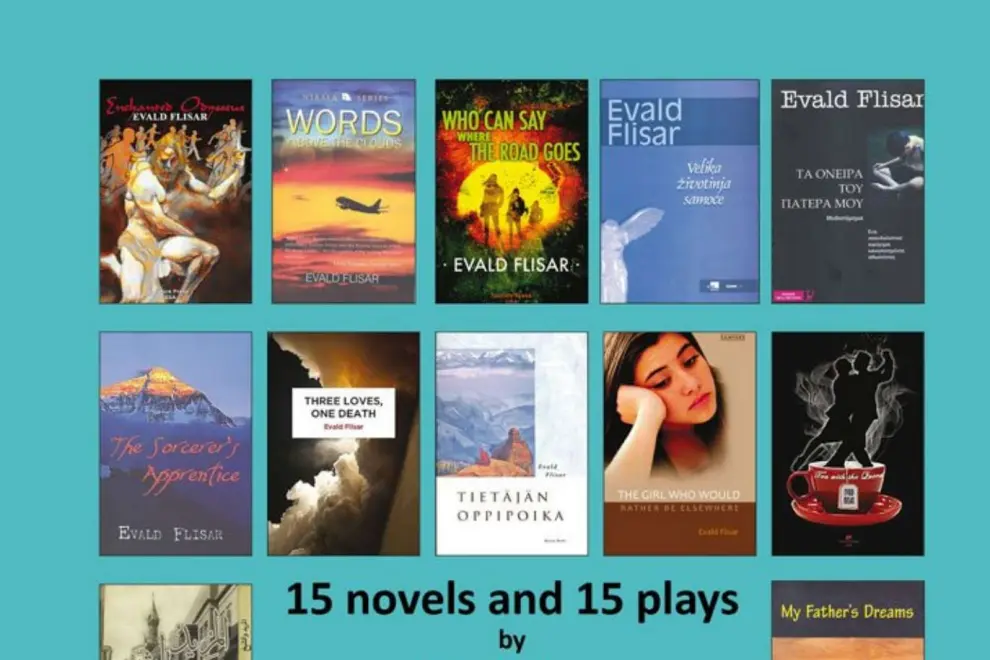

At least one translation of a Slovene book gets published per week. Renowned Slovene authors with most book translations in the recent years are; Evald Flisar, Drago Jančar, Boris Pahor, Goran Vojnović, Miha Mazzini, Aleš Šteger, Mojca Kumerdej...

How have they made it?

Manica K. Musil, illustrator and author of children books which are becoming increasingly known around the world, stresses: "Nothing just happens. A lot of the success builds on international awards, and the consistent effort invested in meetings with foreign publishers." She sees the arts in general as a long-distance race, "...you never know when doors might open or close. I think international literary presence reflects years of motivated work."

What does it mean, how does it feel to be widely translated?

Evald Flisar, the most widely translated Slovenian author and playwright

"I suppose I should be happy with 216 translations of my works into 40 languages, with more on the way. Considering the number of speakers of these languages my novels, stage plays and short stories are available to half of the world's population. Theoretically, of course, since most people don't read. I should also be happy that my works are translated not only into major languages (such as English, German, Spanish, Italian, Russian, Chinese, Hindi, Japanese, Arabic, Indonesian), but also into lesser known (such as Amharic, Malayalam, Nepali, Tamil, Odia, Vietnamese, Icelandic etc.). I should also be happy that my plays have been staged by professional theatres in London, Washington, Cairo, New Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Tokyo, Taipei, Jakarta and other big cities. Evidently there is something in my works that resonates wider than in Slovenia and Central Europe, something that is not localised but touches preoccupations and feelings of all people. In spite of this, the satisfaction I should feel keeps evading me. God knows why. Maybe because I feel that in the world in which we are forced to live literary success is not all that important. Far more important to me are my wife and our talented 14-year old son, a born mathematician. So I am happy, after all, but for a different, better reason."

Drago Jančar, widely translated and internationally awarded Slovenian writer

"I am happy that I am somehow, with my books, at home among the readers in foreign countries and cities, also in the ones I have never visited and might never will. When (in the year 2014) one of my novels was hailed "the best foreign book of the year" by the literary critics in France, it was for the first time that I - not conceitedly, but self confidently - thought that my writing might be more than only sharing a special Slovene historical and contemporary human experience. This makes me happy, of course. However, all the translations and recognitions, are not any help to the author, if he doesn't again and again and with all his creative power fight the substantive and ethical issues as well as stylistic questions that intrigue him. Sometimes it is not that easy. When I want to tell any new story, I am again and again in front of a white sheet of paper, as we used to say, today we would say: in front of the whiteness od the computer screen."

What is the role of translators in international arena?

Tanja Petrič is a translator, literary critic and editor, president of the Slovenian Association of Literary Translators, organization with around 200 members.

She defines translators - especially those who translate from small languages - as extremely important cross-cultural mediators and "literary agents". "The publishers in the countries of the target languages often do not have access to, for example, a book of a Slovene author or, not in many cases, have it - only indirectly, via bridge language English." Even on the western markets is hard to speak about a standardized role of the translators, let alone in other parts of the world, because the book markets and the "culture of translating" are diverse. "Germans, Checks or Croats have a much larger percentage of translated literature than, for example French, English or Americans. Therefore an instant recipe for the success of the Slovenian literature abroad in fact doesn't exist."

Andrej Pleterski, literary translator and cross-cultural mediator

Since the early 90s, there has been a general consensus in Translation Studies that any translator (even one translating nothing but user manuals) can be considered a cross-cultural mediator on account of not only merely engaging in a linguistic process, but also a cultural one. "Yes, in terms of literary translation, there are translators who deliberately refrain from any activity exceeding text-translating whenever possible." As a result, to make a distinction between two categories of literary translators, Andrej Pleterski finds it fitting to call someone both a literary translator and a mediator in the case of a higher degree of agency reflecting in their keeping up to date with the latest book production (both abroad and at home), selecting and proposing texts to be translated, writing forwards to books, compiling anthologies, running translation workshops, giving lectures on translation, hosting literary events, attending literary festivals, escorting their authors, keeping up correspondence with them, applying for translation residencies etc.

"I have been doing most of the above activities, many of them pro bono, going far beyond linguistic exchange, towards cross-cultural mediation. Feeling that general public is unaware of the vast scope of activity this profession can comprise, I am increasingly inclined to calling myself both a literary translator and a cross-cultural mediator, not only enabling communication by translating texts, but also building bridges between individuals and organisations across cultures, thus creating stories on wholly a different level."

Maria Florencia Ferre, translator from Argentina,

became a translator from Slovenian when there was a twist in her life. "I lost my job in 2001, during the economic crisis in Argentina, and I have been a free lancer ever since. This situation allowed me to travel freely and devote time to improve my language training. Even if I couldn't make ends meet I managed to write and travel and learn." In 2005 she joined the "Lektorat" of Slovene language at the university of Buenos Aires and immediately landed a grant for the Seminar of the Slovene language, literature and culture that regularly takes place at the Faculty of Arts in Ljubljana. "Soon after that I met the Študentska založba team, who were thriving in Slovenia and abroad with a wide range of authors and publications and made great efforts to make contemporary Slovenian authors known worldwide." Maria Florencia Ferre gradually became familiar to a variety of poets, novelists and storytellers, and discovered classic authors too. "I had experience in publishing and translating in other areas, namely social studies, and was a writer myself, though a shy one. Aleš Šteger and Mojca Jesenovec encouraged me to start translating." Soon after that she applied for the International Slovenian literature translation seminar founded in 2010 and co-financed by the Slovene Book Agency and she has been its regular attendant ever since.

"Something curious about that decision is that when I was a small child I kept saying to myself I wanted to learn as many languages I could just to read literature in its original language." She never intended to be a translator. "As a teenager, my view was that a translation could never compare to the source language text and that it was not worth trying to find a suitable translation." She read Gottfried Benn's poems in a bilingual edition; "I corrected the translation even if my German was far from even a basic level. If I could go back in time I would have a word or two with that cocky girl."

Why Slovene? "Slovene language fascinated me. I had heard of dual number in ancient Greek when I was studying at the university, but never had to actually use it. At first I had trouble with the lack of articles too. And I had to make a whole new set of associations to find coherent semantic fields within the language." Slavic roots were unknown to her before, and now she is also learning Russian with Slovene as a background.

Her frst attempts to put a Slovene text into Spanish were a couple of short stories by Miha Mazzini, a poem by Dušan Jovanović, the poem Dark door by Lili Novy. "Lojze Kovačič, Edvard Kocbek and Gregor Strniša are readings you do not forget, those who stay with you for a lifetime."

Slovene community in Argentina strives for the establishement of Slovene Literature. When speaking about our books there Maria Florencia firstly sets out Drago Jančar: "Coming out of the novel I Saw Her That Night and writer's visit of Argentina were very attention-grabbing." What about poetry? "Gog y Magog publishing house has published poetry books as a part of a collection of Slovene poets, for 15 years now." She also mentions Martin Krpan: "Translated as Martín Kerpán is mandatory reading at some schools." And - in 2018 Alejandro González, an outstanding translator from Rusian, founded a magazine named Eslavia intended to the most important publications of Slavic literature and literary science. There Maria's translations of excerpts from books written by Samira Kentrić, Veronika Simoniti and Maruša Krese were published.

In the article above we have focused on authors and translators in the process of the promotion of Slovenian literature abroad. We are hereby announcing the third, final part of the presentation of the Slovenian literature on the world map - an article highlighting the engagement of publishing houses and certain public institutions.